On 3 November last year, in distant Montreal, Mila Sandberg-Mesner (22.11.1923 – 03.11.2023) passed away into eternity, just days short of her 100th birthday. Mila Sandberg-Mesner (22.11.1923 – 03.11.2023), our countrywoman from Zalishchyky on the Dniester, who survived the tragic maelstrom of the Holocaust as a nineteen-year-old girl. Later, in overseas emigration, she became a writer, public figure, publicist, and author of the memoirs “Light From the Shadows” and “By the Ways of My Youth”.

Mila was born in Zalishchyky on 22 November 1923, into the family of Zygmund and Fanny Sandberg. The couple raised four children: Rosa (Ziuta) Sandberg-Wasserman, Adolf Sandberg, Lotti (Lola) Sandberg-Wiesel, and Amalia (Mila) Sandberg-Mesner.

The family was quite wealthy; Fanny Sandberg was meant to inherit the rich estate of her own ancestors – her grandfather Gedalia and father Moses Elberger – which was located in the village of Kasperivtsi near Zalishchyky. Unfortunately, Fanny was not destined to become a wealthy heiress – the Elberger family estate was burnt down in 1917 by the retreating, demoralised Russian army.

Mila’s father, Zygmund Sandberg, rented a farm on the estates of the Counts Dunin-Borkowski before the war. In August 1914, the Sandberg family, along with hundreds of thousands of other Eastern Galician refugees, headed west, away from the World War front. They settled temporarily in the town of Zakliczyn, near Kraków. Here, in the winter of 1914–15, the Sandbergs’ youngest son, Adolf, died of diphtheria at the age of five. But thanks to the entrepreneurial zeal of the father, who built a business from scratch in a foreign land supplying horses for the Austrian army, the family survived the war and returned to “Warm Podillia”.

In the 1920s, Zygmund Sandberg built his own mill in Kasperivtsi, and a family house in Zalishchyky, where his youngest daughter, Mila, came into this world. The Sandberg house was located on what was then T. Kościuszko Street at number 9 (now S. Bandera Street). Regrettably, it has not survived to our times. The walls of the “Sandberg mill” in Kasperivtsi are also living out their days in ruin.

In her own memoirs, published in Ukrainian in 2009 under the title “Light Through the Darkness”, Mila Sandberg paints the interwar Zalishchyky in idyllic tones, “my city” – like a mythical Atlantis that disappeared almost without a trace in the fires of the Second World War, political repressions, and ethnic cleansing.

Thanks to its picturesque location in the Dniester valley and its warm climate, Zalishchyky gained fame at that time as a climatic resort, called the “Polish Riviera”.

Before the war, about 6,000 inhabitants lived permanently in the town, over a third of whom were Jews. Upbringing in the Sandberg family was based on respect for all fellow citizens, regardless of their language, descent, faith, or social status. The parents served as a living example in this sense. Fanny Sandberg was the founder and president of a women's charitable organisation for the care of the poor and sick, which operated in Zalishchyky during the interwar period. As a benefactor, Zygmund supported low-income families and orphanages. Mila later recalled that while studying at the local gymnasium, she did not encounter manifestations of inter-ethnic intolerance until the late 1930s.

Mila’s happy childhood ended in September 1939 with the arrival of the Bolsheviks and the practice of lawlessness they introduced: mass arrests, political deportations, and the confiscation of property from wealthier residents. Fearing her father’s arrest as a representative of the “class of exploiters of the working people”, the Sandberg family moved to Kolomyia, where their eldest daughter Rosa lived at the time, and her husband Dawid (Dunek) Wasserman practised medicine. It was in Kolomyia that Mila completed her schooling and received her Ukrainian Soviet school certificate in 1941.

Here she was overtaken by the Nazi occupation, followed by the relocation of the entire family to the ghetto.

In the photo: the police building in Kolomyia, 1942.

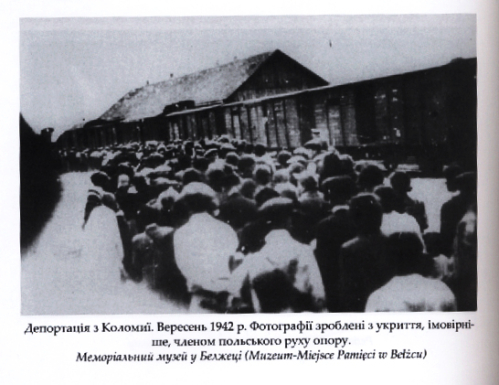

The turning point in the lives of the Kolomyia ghetto prisoners was 10 October 1942. On this day, the third major action to “cleanse” it began, upon the conclusion of which another railway transport with four thousand Jews, condemned to murder in gas chambers, departed from Kolomyia station to the Bełżec extermination camp.

In the photo: prisoners of the Kolomyia ghetto are led to the train that will depart for the Bełżec death camp.

The Sandbergs were just a few days short of realising an escape plan from the ghetto devised by a young acquaintance named Albin Thiel (Thiel, Till), who was in love with Lola Sandberg and tried to save her entire family. Albin had the status of Volksdeutsche, i.e. an “Aryan”, and thanks to this, could visit the Sandbergs relatively freely throughout their imprisonment in the ghetto. The “action” in the ghetto caught their family unawares, so they, along with everyone else, ended up on the “train of death”.

But on that black October night, a quartet of young people in the same wagon of doomed prisoners decided not to submit to circumstances even in a situation of total hopelessness. They dared to escape right from the moving train.

Here is how Mila Sandberg herself recounts this breathtaking episode: “As soon as the carriage doors closed, Jasia (the author’s cousin – O. S.) began to make her way through the crowd to the boarded-up upper window. She immediately began checking if the nails were driven firmly into the boarded window. Olek, my former classmate, helped her handle this work. It took them quite some time to pull out the nails and open the window enough for at least one person to squeeze through. When night fell, the discussion began about who would jump first. My parents decided to stay to the end — to resign themselves to their death. They were tired of constant escapes and hiding. They believed it would be easier for us to survive without them. My mother sat down in a corner and, weeping, said: ‘How will I know that my children, jumping from a train speeding like a mad thing, won't break their bones?’ Then my father spoke, to calm Mum down a little: ‘When my children jump from the train, angels will spread their wings beneath them to soften their fall.’ Then Mum solicitously took off her scarf and bound our feet so we wouldn’t lose our shoes during the fall.

We took the last remnants of bread from our pockets, gave it to them, and hugged them for the last time.

At that moment, it seemed to me that I was in some kind of trance. As if everything froze in a strange calm until the moment we safely found ourselves on the ground… I seemed to be completely unharmed and lay quietly without a single movement, watching the ghost train disappear into the darkness. No signs of alarm sounded from it. On that train, my parents went to meet their deaths.

A few minutes later, I was already running headlong in the direction of where Lola had jumped. Finally, finding each other, we embraced and began to sob bitterly. These were bitter tears of despair and fear. A little later, we went to find Jasia, who was slightly injured. Olek was not as lucky as we were. We found him lying near the rails with a leg broken in three places. We tried with all our might to drag him to a safe place near the forest, but he was suffering terribly from pain and refused to move. Olek convinced us to run away and stated that as soon as we left, he would take the cyanide pill he always carried with him. However, he did not take the poison… When we returned shortly after to the place where we had previously left him, we were struck by a horrific sight — Olek's entire body was riddled with bullets...”

In the morning, the runaways learned they were near the town of Khodoriv. Here, strangers, merciful people, hid the girls for some time, and they even had the opportunity to send a letter to Albin Thiel in Kolomyia.

Albin also did not submit to the tragic circumstances and did not betray his love. He dared to turn to Father Ludwik Peciak, dean of the Catholic parish in Kolomyia, with a request to save three Jewish girls – he needed to issue them fake birth certificates. The priest agreed, as he had agreed to help many other Jews before. In the end, this cost Father Peciak his life – already in November he was arrested by the Gestapo, imprisoned in the Majdanek concentration camp, and later transferred to the Flossenbürg camp, where he died in the spring of 1943.

Thanks to Albin Thiel's desperate help, Mila and Lola hid in Lviv for some time, and later were even able to find legal work as statisticians in the office of the Liegenschaft (agricultural estate management) located in the town of Bibrka…

* *

Albin Thiel was honoured in the post-war period with the honorary title of Righteous Among the Nations.

Mila Sandberg-Mesner also petitioned the Yad Vashem organisation in Jerusalem regarding the recognition of Father Ludwik Peciak. However, a decision on his honouring has not yet been made – allegedly due to a lack of documentary evidence…

*

After the war, Mila Sandberg emigrated via Romania to Canada, settled in Montreal, and married. Her husband was Izydor Mesner, who hailed from Przemyśl. For many years, she worked as a collections manager at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, carrying out an active educational and commemorative mission, and served as a board member of the Montreal chapter of the Canadian Foundation for Polish-Jewish Heritage.

Mila possessed an amazing gift for communicating sincerely with many people, often very different in age, origin, language, and religious affiliation. For many years, she actively promoted humanistic values and shared the rich experience of her life. Her life credo is perhaps concentrated in these words: “I will be glad if my words and actions contribute – even in a small measure – to better mutual understanding between people.”

In the photo: Mila Sandberg-Mesner, Nobel Prize winner for Literature Czesław Miłosz, and Izydor Mesner, Montreal 1967.

All her life in emigration, Mila Sandberg longed for her homeland: “I dream of returning home someday… I miss the past life that we lived happily together there very much.”

But she was able to come to her native land for the first time only 63 years after the war, in 2008. By then, almost nothing reminded her of the city of her childhood. Her Zalishchyky now existed only in memories. Mila was shocked that on the site of the mass grave of 840 Jews, shot in November 1941, a stadium had been built during Soviet times.

Yet, it is important not to submit to circumstances – she decided that this blood-soaked earth must become a place of memory. And a memorial sign to those eight hundred Zalishchyky martyrs was erected two years later.

This project was realised thanks to donations from the Mesner family, other benefactors from Canada, Austria, and Israel, support from the Zalishchyky City Council headed by the then-Mayor Volodymyr Beneviat, and thanks to the help of the director of the Zalishchyky District Museum of Local Lore, Vasyl Oliinyk.

At the opening ceremony of the memorial sign, Mila Sandberg addressed those who would live on this land after us: “You are a new generation, far removed from these horrors. It depends on you whom to choose, who will govern you, what laws will be adopted here, what ethics and morals will guide you and your children. The people who committed and witnessed these crimes are no more. The future of this land, of the world in which we live, is now in your hands.”

* *

3 November marks one year since Mila Sandberg's death. Last year, her friends and relatives initiated an international commemorative initiative – the planting of “Mila Sandberg memory trees” – https://montrealgazette.remembering.ca/obituary/mila-sandberg-mesner-1089024771

Where else should such a tree grow if not in Mila's native city on the Dniester, where her childhood passed, and which she described with such touching warmth and love?

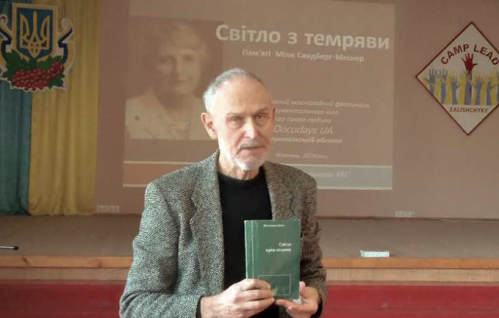

So, on 24 October 2024, “Mila Sandberg Remembrance Day” was held at the Zalishchyky State Gymnasium. The gymnasium audience was presented with a presentation about her life path, as well as the Ukrainian edition of her memoirs, “Light Through the Darkness”.

And near the memorial sign, reminding contemporaries of the Holocaust victims, with the participation of students from the Zalishchyky Gymnasium and students from the Ye. Khraplyvyi Zalishchyky College, a magnolia was planted, a symbolic “Mila Sandberg Tree of Memory”.

At the moment, our little tree is still very small and fragile. But it is already a living monument: to the people whose lives were taken 80 years ago by a misanthropic regime, and also to the Human who gave us the memory of them. For the tree to grow and get stronger, it needs our care and protection – just like memory itself. But we believe – someday our “Mila's memory tree” will blossom. And that means the light she shed into the darkness of oblivion will not go out.

This event took place within the framework of the programme of the Docudays UA International Travelling Documentary Human Rights Film Festival in the Ternopil region.

We sincerely thank everyone involved in this small event. The world has become a little kinder thanks to all of you. We must continue on this path. Let us remember Mila Sandberg's credo – to promote mutual understanding between people. And also – not to submit to evil and tragic circumstances even in total hopelessness...