About the pastoral mission of the Kovch family in the Ternopil region – on the occasion of the 140th anniversary of the birth of Father Emilian Kovch.

It seems the first time we heard about Father Emilian Kovch was in 1999, when He was awarded the title of “Righteous of Ukraine” by the Jewish Council of Ukraine - in gratitude for saving many Jews during the Nazi occupation.

But the heroic story of his pastoral service gained greater resonance already in 2001, when Pope John Paul II during his visit to Ukraine proclaimed Him a Blessed martyr of the church. The Pontiff then noted that the historical figure of Father Kovch is such that “unites us all” - i.e. believers of different religions, citizens of different ethnic origins and inhabitants of different countries. This thought was soon confirmed by patriarch of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church Lubomyr Husar: «This is a son of one people, who perished on the land of another people, and his life was taken because he wanted to help a third people. Where there are saints, there are no more borders».

In 2008, the Synod of the UGCC proclaimed Emilian Kovch the patron saint of pastors of the Greek Catholic church. Since then his name has become quite well known in Ukraine. Over the last two decades a large number of media publications have appeared which generally reflect his life path and worldview, although at times abounding with errors and overgrown with fabrications. However, until now neither in Ukraine nor abroad has a thorough scientific biography of our great Righteous One been compiled. No feature film based on such a biography has been created. To this day we know little about his family circle, about people who influenced the formation of his personality.

Finally, almost nothing is known about the priestly dynasty of Kovchs, whose paths of service often passed through the Ternopil region. So this modest publication should arouse interest and prompt proper honouring of the memory of the pastoral mission of the Kovch family in our land, using the news hook: the 140th anniversary of the birth of Father Emilian, which should have been celebrated at the state level by decision of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, as well as the 80th anniversary of his tragic death, which also fell on 2024.

Of course, the goal of the author of this post consists not only in reminding of anniversary dates. More important is to emphasize that those spiritual values which the historical figure of Father Emilian Kovch vividly embodies are genuinely relevant today. His patriotism, nourished by love, not hatred – like love for one's own without contempt for the other. His solidarity with all humiliated and oppressed - without looking at their origin… His respect for human dignity and sacrificial service to people… We are speaking about values which are truly capable of overcoming borders between different people and nations. Moreover, proclaimed by Him not only in church sermons, but confirmed by many of his personal actions in incredibly difficult life circumstances - when in most people the instinct of self-preservation turns out stronger than moral norms. After all, only in few chosen ones does the spirit win. Them we name heroes and traditionally imagine armed, with sword in hand. Father Kovch at first glance looked unarmed in his solitary non-submission to brutal violence brought to his land by two despotic regimes, Bolshevik and Nazi. And yet his humanistic spirit did not yield to violence. Hence - to be a hero, it is not necessary to carry a sword.

Today, when Ukraine is experiencing another tragic page of its own history, when crimes against humanity are committed daily, many of us also face a difficult choice: to submit to cruel circumstances, or to resist them? To help another, or to save oneself at the cost of others? To accept evil, or to answer it, and if to answer, then how?… The example of people who once survived similar trials and emerged from them with dignity can help make this choice. Such a person, beyond any doubt, was Father Emilian Kovch. We can be fully proud of Him. We can strengthen our spirit on his worldview and deeds. With Him, finally, we could worthily present ourselves as a cultural nation to the whole world.

So it is high time: studying his life path and spiritual heritage, honouring the memory of Him - truly an apostolic figure in modern Ukrainian history.

* * *

In open sources today it will not be difficult to find certain biographical information...

Kovch Emilian (Omelian), born 20.08.1884, martyred 25.03.1944 – priest of the Greek Catholic church, Ukrainian patriot, educator and public figure, humanist, chaplain of the Ukrainian Galician Army, long-time parish priest of the town of Peremyshliany, unconditional saviour of Jews during the Nazi occupation, voluntary pastor in the Nazi death camp Majdanek…

The father of the future pastor was Father Hryhoriy Kovch (1861 – 1919), also a Greek Catholic priest and extraordinary public figure, about whom we will tell further. At the moment of birth of the first-born son, named Emilian at baptism, Father Hryhoriy served as assistant priest at St. Paraskeva Church of Pistyn deanery, in the village of Kosmach, Kosiv county. His wife was Mariia Kovch (? – 1939), from the Yaskevych-Volfeld family. The date of birth of Mariia (1891), provided by Ukrainian Wikipedia and duplicated by almost all other sources, Ukrainian and foreign, is definitely erroneous, but for some reason no one pays attention to this. The Kovch couple had five children: brothers Emilian and Eustachiy, sisters Olha, Sofia and Nataliia.

Doubt is also raised by the common assertion that little Emilian began school education in Kosmach. After all, at the moment when he had not yet turned half a year old, the Kovch family left this mountain village. In January 1885 Father Hryhoriy received regular appointments to village parishes of Tysmenytsia deanery in Pokuttia, where he served until 1889 and from where he moved already to Podillia.

But what is probable is that Emilian received school education in a German-language six-year school in Kitsman – perhaps precisely from here comes his good command of German, noted by contemporaries. In many biographers of Father Emilian we find a report, though unsupported by documentary sources, that in 1905 he passed the matriculation exam at Lviv Academic Gymnasium. However, the fact that gymnasium student Omelian Kovch completed studies in the eighth, i.e. graduating class of Kolomyia Ukrainian Gymnasium, and successfully passed the final exam precisely there, is documented by the “Report of the 2nd I.R. Gymnasium in Kolomyia for the 1903 – 1904 school year”.

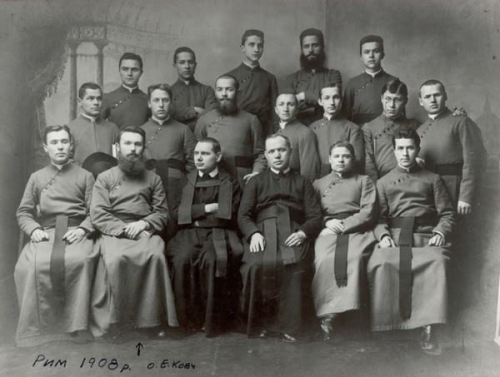

After completing the gymnasium course, using the scholarship of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, Emilian set off for Rome, where he settled in the College of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus on Piazza Madonna dei Monti and for six years studied philosophy and theology at the Pontifical Urban University (1905 – 1911).

After graduating with a doctoral degree in philosophy and theology, he returned to his native lands and was ordained a priest in Stanyslaviv Cathedral by Bishop Hryhoriy Khomyshyn (1911).

While still a student, Emilian marries Mariia Anna Dobrianska, daughter of a Greek Catholic parish priest from Bukovyna land. In the following years the family raised six children.

Father Kovch’s first post in his priestly service during 1911–1912 was at the Holy Trinity Church in the Skalat deanery, located in the Podolian town of Pidvolochysk on the Zbruch River – this marked the beginning of his path of service in the Ternopil region!

Father Emilian dedicated the next four years to missionary work among Ukrainian settlers in the Bosnian town of Kozarac, where the Great War found him. Following the repulse of the Russian army's offensive in 1916, he returned to Galicia and served for some time as a vicar in the parish of the village of Sarnyky Horishni in Rohatyn county.

However, hopes for peaceful priestly and educational work in the post-war province were dispelled with the outbreak of another war – the Ukrainian-Polish war for Eastern Galicia. Inspired by his father's example, Father Emilian volunteered as a chaplain for the Galician Army of the West Ukrainian People's Republic (ZUNR). By the end of 1918, he was already serving with the rank of lieutenant in the Berezhany kish of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (USS) brigade, part of the 2nd Corps of the Ukrainian Galician Army (UHA). It was indeed then that his passionate nature for caring and bestowing kindness upon people became vividly apparent. This is how his fellow serviceman Roman Dolynskyi recalls him: “Father Kovch, young at the time, was full of energy and strength. There was no corner in the Kish where our Chaplain would not appear several times a day. There was no sector of the complex life of the Kish in which our Chaplain would not take a responsible part. Every morning, after celebrating the Divine Liturgy, Fr. Kovch hurried to the hospital, which was already full of participants in the battles for Lviv. Every day he could be seen on the training field, in the office, in the warehouses; everywhere he resolved the complaints of individual units or soldiers, always finding time for the soldiers and resolving their grievances with his authority and ability...”

With the Galician Army, Father Emilian walked all its paths, both glorious and tragic: through the retreat from Lviv, the victorious but brief Chortkiv Offensive, the crossing of the Zbruch, the typhus epidemic, the search for situational allies among various warring forces, captivity, and the internment camp... Several times on these paths, he found himself facing death. Once, having fallen into Bolshevik captivity, he was already heading in a freight train with hundreds of other prisoners into the unknown, about which he later recalled: “The train stopped in the middle of a field to clear the wagons of the dead and give water to the wounded. Having asked the guard to allow me to drink water and breathe fresh air, I found myself outside near the wagon, and when the train was about to move, the guard closed the wagon door in front of me, thereby saving my life... He even shouted: ‘Batyushka [Father], remember to pray for Luka!’ But I did not manage to run far — that same day I was seized by another Red detachment and added to a group of captives being prepared for execution. Everyone was taken to the forest and forced to dig their own graves. At the penultimate moment, when the prisoners were ordered to turn their backs to the firing squad, I read a prayer aloud and gave the signal to flee. Everyone condemned to be shot rushed to escape...”

In 1920, field chaplain Kovch, like the majority of officers of the Galician Army, was interned by the Polish administration in a camp. Which camp this was exactly is currently unknown. His daughter Anna Maria Kovch-Baran, in her memoirs published overseas, described the dramatic circumstances of her father’s return to his native lands as follows: "Finding himself in a Polish prisoner-of-war camp, father fell ill with typhus. After several weeks in a military hospital, he managed, with the help of kind people, to get to his sister Olha in the village of Tsapivtsi (Zalishchyky district), where his brother-in-law Fr. Antin Nakonechnyi was the parish priest after the death of grandfather Fr. Hryhoriy Kovch. Here he fell ill with typhus again, burning with fever. Risking getting sick themselves, sister Olha and brother-in-law Antin did not leave his bedside. When the family informed our mother about father's return from the war and his typhus illness, mother, who at that time was with the children at her father Fr. V. Dobrianskyi's in Chernelytsia, immediately went to visit him. It was early spring of 1920. The ice on the Dniester was already fragile. To get from Chernelytsia to Tsapivtsi, one had to cross the Dniester. The boatmen refused to venture into the water among the ice floes. And she, taking a boat, decided to go herself. But, having neither experience nor strength, at the first encounter with the ice, she began to sink. Seeing the danger, a brave man – a ferryman from Ustechko – rushed after mother, pulled her onto his boat and in such a risky situation by some miracle both reached the other bank... Seeing father, mother at first did not recognise him – he looked more like a ghost than a person, and she lost consciousness for a while: he was a skeleton blackened from excessive fever... But with God's grace and the help of the people of Tsapivtsi who responded to the misfortune, father began to recover.”

So, after recovering, Father Kovch returned to his family and peaceful priestly work. In 1922, he received an appointment as the parish priest of the Church of St. Nicholas in the town of Peremyshliany.

Most of his biographies state “Peremyshliany near Lviv”, “47 km from Lviv”, but here we allow ourselves a small clarification: in the interwar period (1920 – 1939), the town and county of Peremyshliany were part of the Tarnopol Voivodeship. This period in history left behind a certain legacy which cannot be clearly separated either from the history of the Ternopil region or from human memory. Specifically regarding Father Emilian Kovch's pastoral ministry in Peremyshliany, it covers the longest period of his life (1922 – 1943). It was here that he most fully realised himself as a pastor, a great humanist, and a public figure, leaving behind grateful memories among descendants. Thus, we, the current residents of the Ternopil region, should not forget his traces on this land and should support that memory in every possible way.

At that time, Peremyshliany was a typical East Galician town where the Jewish population constituted the majority. According to the 1921 census, there were 2,051 of them. Their centuries-old presence in the region was personified by the building of the Main Synagogue from the 17th century.

Also enjoying deserved authority among all the town's residents at that time was the local parish priest of the Roman Catholic Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, Fr. Zygmunt Bilski, who dedicated more than half a century of his life to pastoral service to the community of Peremyshliany. It is therefore not surprising that in the 1920s many local Greek Catholics converted to the Roman Catholic Church.

The Ukrainian community of Peremyshliany, after the cessation of wars which lasted for six years and led to the destruction of the region's economy, was going through particularly difficult times. The defeat in the struggle for their own statehood weighed heavily on patriotically minded Ukrainians. As is known, by the decision of the Paris Peace Conference and the Conference of Ambassadors of the Entente, the Polish Republic incorporated Eastern Galicia into its borders “to protect the civilian population from the danger of Bolshevik bands”, whilst simultaneously undertaking to resolve the future fate of the region in a referendum. That is, for the first time in history, a state pledged to the international community to respect the rights of a national group. However, neither mechanisms for monitoring the observance of minority rights were established by the international community, nor was the referendum appointed by the Polish authorities, and even the issue of granting administrative autonomy to the three Galician voivodeships was subsequently constantly sabotaged. All this fuelled the confrontation between representatives of the two peoples who had lived on this land for centuries and provoked Ukrainians to protest.

Father Kovch, with his characteristic maximalism, could not stand aside from these problems. For this reason, already in 1922, at the very beginning of his priestly work in Peremyshliany, he stood trial for an “anti-state act”. On the eve of Easter, the local administration placed a poster with announcements regarding the incorporation of Galicia into the Polish Republic and the holding of elections to the authorities - right opposite the Church of St. Nicholas. Father Kovch publicly tore down that poster on his way to church. Upon receiving a summons to court, he suggested inviting a Roman Catholic priest as a witness. During the hearing of the case in court, Father Kovch commented on the incident roughly as follows: “It was Good Friday. We have the Epitaphios [Shroud] brought out and the Most Holy Sacrament displayed. I am walking to the church, and people have turned their backs to the Holy Sacrament and are reading some paper. I flew into a rage and tore down that paper, and now it turns out that this is an anti-state act”.

Further, Father Emilian addressed the priest:

– And what would you have done, Father, in such a case?

– Just as you did, – he replied.

The court agreed with the argument that the local administration should respect the religious feelings of citizens and not provoke them into protest actions, so Father Emilian was acquitted. This case well illustrates the fact that despite the unresolved national question in interwar Poland, that state was governed by the rule of law. Citizens in it had the opportunity to defend their rights in court. It is not hard to imagine what fate would have befallen Father Emilian had he started tearing down posters with government decrees in the Bolshevik “republic”.

Despite constantly tense relations with the authorities, Father Kovch, being a conscious Ukrainian patriot, treated all the town's residents with kindness, regardless of their religion and ethnicity. He was an open opponent of xenophobia and antisemitism, trying to maintain a tolerant attitude towards representatives of other ethnic groups in a situation of socio-political tension that was constantly growing in the interwar years. Father Mykola Diadio, parish priest of the village of Lahodiv in Peremyshliany county, testified about him with these words: “Everyone loved Father Kovch – Ukrainians, Poles, Jews, whoever it might be. Father Kovch did not care about himself, and often not even about his relatives, but did good to everyone who turned to him.”

Faina Liakher, who was raised in a family where Jewish tradition prevailed, but later studied at the Peremyshliany gymnasium together with Father Omelian’s children, also noted the warm and friendly attitude on their part. Communicating with peers in that oasis of mutual understanding formed around the parish priest and his family later helped her survive the years of the Nazi genocide.

From the beginning of his ministry in Peremyshliany, Father Omelian was immersed in daily work and caring for those who needed help most. Within a short time, he managed to restore the St. Nicholas Church (early 19th century) in the town and the Church of John the Baptist in the suburban village of Korosno, both neglected during the war years, to restore the Narodnyi Dim [National Home], to set up a “Prosvita” reading room, to create a cooperative, to found church and gymnasium choirs...

In 1919, in the village of Univ, seven kilometres north of Peremyshliany, on the initiative of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, the Univ Monastery of the Studite Brethren was founded, later becoming the Holy Dormition Univ Lavra from 1926. Metropolitan Andrey's brother, Archimandrite Klymentiy (Kazymyr) Sheptytsky, served as the abbot of the monastery until 1937, and the Peremyshliany parish priest shared many years of friendly relations with him. Andrey Sheptytsky also visited Peremyshliany and Univ more than once. One of the photos depicts him among believers together with Omelian Kovch.

The cause of creating a network of Studite monasteries in villages, initiated by the Sheptytsky brothers, had a high goal – to create centres of Christian spirituality, human brotherhood, ascetic life, living not only on alms but by the work of one's own hands. Undoubtedly, their example and communication with them had a great influence on Father Kovch and other priests of the Peremyshliany deanery. After all, they regularly visited the Univ Monastery during pilgrimages, got involved in its development in every possible way, and helped maintain the orphanage and craft school that operated at the monastery.

But secular, particularly political life, lacked the harmony carefully maintained within the monastery walls.

The year 1930 proved to be acutely critical in the political life of Poland, marked by the radicalisation of the “Sanation” regime in the struggle with internal opposition, strengthening of authoritarian tendencies in state governance, press censorship, forced dissolution of the Sejm, arrests and imprisonment of opposition politicians, and on the other hand – radicalisation of the regime's opponents. The government justified the strengthening of dictatorship by the destabilisation of the state by the opposition, which then had strong representation in the Sejm. And also – by the actions of the nationalist and communist underground, primarily UVO-OUN [Ukrainian Military Organisation - Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists] and communists, in whom the authorities saw agents of Berlin and Moscow. In the summer and autumn of 1930, a wave of acts of sabotage and diversions swept through the East Galician voivodeships: arson of grain in estates of lords and settlers, as well as damage to communication lines. An armed attack by an OUN combat unit on a postal carriage in Bibrka gained significant resonance in the vicinity of Peremyshliany, during which a police guard and a participant in the attack were killed. The authorities were quick to place collective responsibility for the terrorist attacks on the entire Ukrainian population of the region. The brutal “pacification” of Ukrainian villages was accompanied by mass arrests, pogroms, and the closure of legal Ukrainian organisations.

The Ukrainian political elite and the public were divided in their assessments of the crisis situation and their vision of ways out of it. All legal Ukrainian parties and spiritual leaders Andrey Sheptytsky and Hryhoriy Khomyshyn came out condemning the activities and methods of OUN/UVO and at the same time emphasising the unacceptability of punitive methods used by the authorities.

Father Kovch was not afraid to publicly condemn the so-called “pacification” in his sermons, for which he was eventually imprisoned for several months in Berezhany prison. Whilst in prison, he did not waste time – right in the cell he wrote a text in which he tried to answer the question about the challenges of the time for the church, to formulate moral and ethical principles that a spiritual father should follow. These reflections of his were published in 1932 in the form of a brochure entitled “Why do ours run away from us?” The title of the brochure highlights the problem of many Greek Catholics converting to the Latin rite. Father Kovch does not blame these people; he tries to outline the reasons for the church's loss of public authority. And he comes to the conclusion that the main one is the orientation of church ministers towards ritual acts, their detachment from the life of communities: “If a priest wants to keep his flock in the faith, church and rite, he must ‘come out of the sacristy’ and must take a lively part in the civil life of his parish. There is no remedy for this! If he does not do this, he will lose the ground under his feet, as has already happened to more than one...”

In the mentioned brochure, Father Emilian also formulates fundamental values that form the basis of his spiritual sermon, which he considers most important for a person who believes in God: “He who sows the wind reaps the whirlwind. He who sows wheat gathers wheat. Similarly, he who sows love will reap love, even if this harvest is late. From this, it follows that just as every work, not only of a priest but of every believing Christian, must be based on love, so his national work dare not be devoid of this basis...”

Unfortunately, not everyone heard the words of the humane sermon that the Church Fathers tried to convey to their faithful. Thus, the signs of trouble over the land became more distinct from year to year.

Another tragic page in the history of the region, with unprecedented scales of lawlessness and dehumanisation, was opened by the Bolshevik regime, and subsequently continued by the Nazi one. Already in September - October 1939, the NKVD began mass arrests in Peremyshliany of the most authoritative people, public figures, intelligentsia, confiscation of property of wealthier entrepreneurs, mass deportations of families of Polish settlers, civil servants, military, policemen. In September, the monks of the Univ Lavra experienced several days of pogrom, during which grain, agricultural machinery, cattle, land were confiscated, and books from the monastery library were seized... The heads of the occupation authorities also actively provoked poor peasants to lawless and inhuman actions with calls to “loot the loot!”

Cases of robberies by lumpenised people of Polish homes abandoned during deportations occurred both in Peremyshliany and in the village of Korosno, whose parish was also cared for by Father Emilian. He painfully experienced these events, saw in what happened a part of his own guilt, and spoke about it with great pain in sermons, demanding the return of taken property: “It seemed to me that I was raising you to be good parishioners, but I have made you a rabble! I am ashamed of you before the Lord God!” Regarding this, Anna Maria Kovch provides a comment from three educated residents of Peremyshliany who found themselves together in Anders' army: gymnasium teacher Masliak, vice-starosta Slomski, and lawyer Brendel. When asked which of the high dignitaries of Peremyshliany behaved best during the Bolshevik occupation, their answer was unanimous - Father Kovch.

The scale of Stalinist repressions reached its apogee in June 1941. The NKVD carried out arrests and killings in Peremyshliany and surrounding villages; on June 26, a mass execution of prisoners took place in Zolochiv prison, mostly Ukrainians, but there were also many Poles and Jews among them. The intention of the NKVD officers who came to arrest Father Kovch was hindered only by a German air raid. When bombs began to fall nearby, the operatives scattered. Father Omelian hid until the arrival of German troops in the house of a Peremyshliany benefactor named Demko, thanks to whom he managed to survive.

On July 1, when the Bolsheviks had already left the town and the German army had not yet entered it, local residents discovered a fresh grave next to the NKVD building, in which 20 bodies of prisoners were found.

The Nazis actively spread the propaganda cliché about the role of “Jewish Bolshevism” [Zhydokomuna] in Stalinist crimes. So Peremyshliany in the first days of the Nazi occupation, like many other Galician towns, suffered a Jewish pogrom provoked by the Nazis and committed by the hands of the local population.

This was the beginning of the end of the centuries-old history of the local Jewish community.

The conscious part of the Ukrainian community tried to stop the street violence. Father Kovch, together with Mykhailo Shkilnyk, a long-time judge of Peremyshliany who was appointed burgomaster of Peremyshliany, set about creating a unit of Ukrainian militia to maintain public order. But it was not easy to stop the launched machine of lawlessness. Already in those July days, Father Emilian warned his countrymen against excessive illusions regarding the new occupier, understanding well his misanthropic essence. Those warnings of his were often recalled later: “Don't rejoice too much, one ‘benefactor’ has been replaced by another, only the buttons on the uniforms have changed”.

Other church figures in the Peremyshliany region also publicly condemned the murders of Jews. The parish priest of the village of Univ during this period was Hieromonk Herman (Budzinskyi). It is known that upon learning about the first murders of Jews, he spoke out condemning these crimes at a general village meeting convened to elect a soltys [village head].

On July 4, 1941, Wehrmacht soldiers set fire to the Main Synagogue, located next to St. Nicholas Church, during a service. His daughter Anna Maria also recalled this: “Father noticed smoke near the church and at the same time heard despairing screams. several Jews ran into the house in great panic and began to beg father for salvation. The Germans, having thrown incendiary bombs into the synagogue where they had just gathered for prayer, closed the doors and would not let anyone out. Without thinking for a moment, father ran there... There was no other thought in his head except that people are burning and asking for salvation. He ran into the crowd near the synagogue and shouted in German, which he knew perfectly, to the soldiers to leave it. Surprisingly, the soldiers got on their motorcycles and drove off towards their station...” Amidst the fire and frantic screams, Father Kovch rushed to open the doors blocked by a heavy post, ran inside and, together with others, began pulling out semi-conscious people, shouting repeatedly: “Run, wherever you can!”

To this day, the exact number of deaths during those tragic events is unknown. Some memoirs mention 10 victims of that Nazi crime. We know that the son of the Belz Rabbi Aharon Rokeach – Moshe – perished in the fire.

The first “action” of mass murder of Jews was committed by the Nazis and their accomplices on November 5, 1941. On this day, on the outskirts of Peremyshliany towards the village of Korosno, at the forest edge in the Berezhyna area, between 300 and 400 men of various ages were shot. Soon a ghetto was established in Peremyshliany. A forced labour camp for Jews began operating in the nearby village of Yaktoriv. In 1942, the deportation of Jews from the region to the Belzec death camp began. The bloody orgies of the first pogroms “evolved” into organised, technological forms of genocide.

But in the darkness of cruelty, lawlessness, denunciations of one's erstwhile neighbours, the fire of human mercy and salvation did not completely fade. One of those who carried this fire was Father Kovch. He called for mercy during sermons, supported people's faith in the victory of good, in the inevitable defeat of criminal regimes. As early as 1941, he prophesied the Reich's defeat in the war: “The morally fallen world is rolling down an inclined plane to its destruction. You, young ones, keep God in your souls, and with His Holy Name go against the whole world when it is against God”.

Thanks to the help of various people, among whom were Poles and Ukrainians, Studite Fathers and nationalists, priests and teachers, peasants and even collaborating officials, several dozen Jews were able to save themselves in the vicinity of Peremyshliany and Univ. In its scale, this was a true underground movement of resistance to the regime and human solidarity. Within the network of Studite monasteries, it was possible to create a holistic system of hiding places for Jews, coordinated by Andrey and Klymentiy Sheptytsky. Thanks to it, according to approximate estimates, about 200 human lives were saved.

It was by the Metropolitan's order that Kurt and Nathan Levin, sons of Ezekiel Levin, the rabbi of the Lviv synagogue “Tempel”, who was a close friend of Andrey Sheptytsky, were saved by Studite monks. Rebbe Ezekiel himself perished on July 1, 1941, on the first day of the Jewish pogrom in Lviv, in the courtyard of the “Brygidky” prison. But his two sons were cared for during 1942 – 1944 by Hieromonk-Studite Marko Stek and personally by Archimandrite Klymentiy Sheptytsky.

A striking example of rescue in Univ is also the story of the Jewish girl Faina Liakher. She was hidden by sisters of the Studite Rule in their daughter house in Univ and in the Holy Protection Monastery in Yaktoriv. After the war, Faina Liakher converted to Christianity and joined the community of Studite sisters.

Four Jewish children survived the entire time of the Nazi occupation in the orphanage at the Univ Lavra.

The couple Wolf and Perla Liam with their four children managed to hide for a long time in the attic of the monastery tannery in Univ.

An example of long-term hiding of a group of Jews is also the heroic deed of local teacher Mykola Diuk. For fifteen months, from January 1943 to June 1944, he hid five Jews in the attic of the Univ village school, and in the basement during winter. Among them were a teacher from Zolochiv Klara Safran with her son Roald. By the way, Roald Safran is that very famous countryman of ours whom the whole world knows as the winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1981, Roald Hoffmann.

Jews also hid in the forests surrounding Univ. Studite monks helped them with food and clothing. When someone among the local residents reported this to the Gestapo, searches and punitive actions took place. One of them ended with the burning of the wooden skete near the Univ Lavra.

There were many stories of rescue and we will probably never know most of them. Only a few rescuers were honoured with the title Righteous Among the Nations.

These are Klymentiy Sheptytsky, Studite monk Marko Stek, teacher Mykola Diuk, residents of Peremyshliany: Mariia Leskiv, Anna Rybak, Marian and Vladyslava Slonetsky, Tadeusz Jankiewicz, Zenon, Yevheniia and Zbihnev Kalinsky...

Their ways of helping disenfranchised Jews, who were denied the right to live, were varied: hiding, supplying food, medicines, producing fake “Aryan papers”, sending them to forced labour in Germany...

Father Kovch, undoubtedly, also resorted to secret assistance and rescue. For example, the fact of his producing fake metrics for the couple Rubin and Itka Pizem, thanks to which they managed to survive, is known.

But how he differed from other Righteous ones is that he was not afraid to show his mercy openly, publicly! To speak about the sin of murder, denunciation and robbery in a church sermon, to publicly baptise Jews and issue them baptism certificates, to admit Jews to his church!

This is precisely what caused fury among the Gestapo men. Of course, Father Emilian's stance was not perceived with approval by all compatriots, and there is ample evidence of this. Even the closest family members asked him to stop, not to expose himself to danger. But he was convinced that a priest, a bearer of God's word, cannot act otherwise! God's word must not hide! He responded sharply to such requests even to his own son Myron, a seminarian at the time: “I was glad of your choice to become a priest, but unfortunately, you still do not understand your priestly vocation, so leave the seminary, choose another path...”

So it was not difficult to predict Father Kovch's further fate. In January 1943, the security police arrested him and imprisoned him in the Lontskyi prison, about which he informed his family asking them not to petition for his release: “I live on the 2nd floor, window 6 and 7 on Sapieha Street, counting from Tomicki Street...” After petitions from many people, including Metropolitan Andrey, the police agreed to release Father Emilian, but on the condition that he refuse further public assistance to Jews. A calm refusal was received from him: “Listen to me... — he said to the SD officer — You are a police officer. Your duty is to seek criminals. Please, leave God's affairs in God's hands”.

Torture could not break the unwavering stance of the Righteous one. One of his cellmates later testified: “Something incredibly heavy was happening in our hearts when we saw the Gestapo men throwing the priest, like some thing, and not a human being, into our cell after torture. We helped him sit down. No depression was visible on his face, some unearthly smile illuminated his face. He comforted us, the young ones, prayed in a low voice for us, for his flock”.

Finally convinced that Father Emilian's spiritual strength would not yield to torture, the Nazis transferred him to the Majdanek death camp, located in the Lublin District of the occupied General Government. From here, as is known, it was “possible to leave only through the chimney of the crematorium”. Here he spent the last months of his life as a prisoner under camp number 239914, in barrack 14 of field 3. Even here, in inhuman conditions, one step from death, he did not abandon his pastoral mission: he continued to celebrate services, pray, hear confessions, baptise, give communion, bring advice and support.

To all attempts by loved ones to secure his release, he replied as before, unshakeably: "I understand that you are trying for my liberation. But I ask you not to do anything in this matter. Yesterday they killed 50 people here. If I am not here, then who will help them go through these sufferings?... I thank God for His kindness to me. Except for heaven, this is the only place where I would like to be. Here we are all equal - Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Russians, Latvians, Estonians. Of all present, I am the only priest here... Here I see God, Who is one and the same for all, regardless of the religious differences that exist between us. Perhaps our Churches are different, but in all of them reigns the same great Almighty God. When I celebrate the Holy Mass, they all pray together. They pray in different languages, but does God not understand all languages? They die in different ways, and I help them cross this bridge into eternity. Is this not a blessing? Is this not the greatest crown that the Lord could place on my head? Precisely so! I thank God a thousand times a day for sending me here. I dare not ask Him for anything more. Do not worry about me - rejoice with me!"

Father Emilian Kovch died in the camp infirmary on March 25, 1944.

Undoubtedly – He fully deserved that future generations speak of Him as a great Righteous one. After all, the Righteousness of life lies precisely in the unquestioning bestowing of Goodness upon people. By his own self-sacrifice on the path of this bestowing, he earned that we do not forget this. For we have a chance to defeat brutal violence only when we remember and value the bearers of Goodness in our history. Father Emilian is one of them.

So give rest, O God, to the soul of Your servant Emilian where the righteous repose.

And make his memory eternal.

And glory.

Monument to Father Kovch on the Avenue of the Righteous at Majdanek, Lublin

* * *

In concluding this post, it is worth mentioning the pastoral mission of other members of the Kovch family in the Ternopil region, primarily Father Emilian's father - Hryhoriy Kovch. After all, the influence of a father's personality on a young person's choice of life path and ideological landmarks is always significant. Subsequently, education, personal experience, and the living example of other people endowed with wisdom and spiritual strength are superimposed on this influence. We can assume that such figures for Father Emilian were Bishop Hryhoriy Khomyshyn, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, Archimandrite Klymentiy Sheptytsky.

But obviously, in his young years Emilian Kovch grew up predominantly under the positive influence of his father. Moreover, Father Hryhoriy also appears to be an extraordinary figure.

Currently, information about his life path is very fragmentary. But we hope - he who seeks will find more.

Birth: March 30, 1861, village of Malyi Liubin, Horodok county – Death: December 19, 1919, town of Starokostiantyniv, Podolian governorate.

Parents: Dmytro Kovch (1827—1888) and Mariia née Koryliak (1831—1891). The father's peasant family was wealthy: they had much arable land, forest, a large apiary (over 100 hives). Dmytro Kovch served as a sacristan at the Holy Trinity Church, organised the rebuilding of the church after a fire in 1885, and donated a considerable amount of his own funds to it. In gratitude for these merits, on the proposal of parish priest Fr. M. Helitovych and landowner K. Brunicki, he was buried in the churchyard after his death. The grave has been preserved.

It is unknown where exactly Father Hryhoriy Kovch received his spiritual education. Ordination to the priesthood took place on October 7, 1883.

First appointment – administrator of the parish in the village of Dobrostany, Horodok county from November 1, 1983 to February 26, 1884.

Next - assistant parish priest at St. Paraskeva Church in Pistyn deanery, located in the village of Kosmach, Kosiv county. Here he served from February 26, 1884 to January 1, 1885. Here his eldest son Emilian was born.

To this day, unfortunately, neither the parish house of the 19th century nor the mentioned historical church of Paraskeva has survived.

I recall how back in 2004 the author of these lines happened to visit Kosmach, the Hutsul village where Emilian Kovch came into the world. Already then the office of Kosmach village head Dmytro Pozhodzhuk was adorned with a portrait of Father Emilian. However, the idea of naming the Kosmach comprehensive school after Father Emilian at that time did not receive support among the teaching staff...

In the following years, Father Hryhoriy served in Tysmenytsia (from January 1, 1885 to 1887), in the village of Hannusivka, Tysmenytsia county (from 1887 to 1889), in the village of Roshniv, Tysmenytsia county (from 1889 to October 4, 1889).

And already from 1889, the period of priestly service in Podillia begins, the longest in his life – interrupted only by missionary activity in Bosnia and chaplaincy service in the Ukrainian Galician Army. It began on October 4, 1889, in the village of Davydkivtsi, Chortkiv county, where Father Hryhoriy served for almost a year as parish administrator, until September 30, 1890. This was followed by 4 years of service as assistant priest in Husiatyn at the historic Onufriyivska Church (1890 – 1894).

Father Hryhoriy devoted the most years of his life to pastoral work in the village of Lysivtsi, Zalishchyky county (from 1894 to March 9, 1908). Here he held the position of parish priest, and subsequently also Zalishchyky Dean. Vasyl Sopivnyk, author of the book “Lysivtsi Spiritual Source”, mentions his merits for the village with great respect: “The flowering of the Greek Catholic faith in the village falls on the ministry of Fr. Hryhoriy Kovch here. He worked zealously in the bosom of Christ's vineyard, fully dedicating himself to pastoral duties. The priest, as chroniclers write, was at that time the only moral leader of the community. Against this background, his energetic activity looked like a small but bright torch...”. Consistently, Fr. Hryhoriy also implemented school policy based on the national idea and its leaders. In 1907, Fr. Hryhoriy Kovch headed the “Prosvita” societies in Lysivtsi and Shypivtsi. He was friends with the director of the school in Lysivtsi, Vasyl Khraplyvyi, from whose family came famous world scholars and public figures.”

Dr. Lonhyn Horbachevskyi also recalls Father Hryhoriy's civil and educational work, known throughout the entire Zalishchyky county, in his memoirs “My Life Path. For my children and grandchildren in memory”, published in Canada. We have grounds to conclude that in Lysivtsi, Father Kovch Sr. had already fully realised himself as an educator and public figure.

But about his participation in political affairs there was no information until now. So we must talk about this in more detail.

It turns out that Father Hryhoriy Kovch in 1899 was one of the founding members of the Ukrainian National Democratic Party as a representative of Zalishchyky county. From history we know that in December 1899 at the constituent congress in Lviv, the Ukrainian National Democratic Party (UNDP, or “Party of Narodovtsi” [Populists]) was formed. Its initiators and leaders at this stage were Yuliian Romanchuk, Kost Levytskyi, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Yevhen Olesnytskyi and others, as well as Ivan Franko, who by that time had become disillusioned with socialist ideas.

In the newspaper of the Narodovtsi “Dilo” dated 17.09.1933, No. 244, one can find memoirs about this event by Dr. of Law Yuliia Olesnytskyi titled “The First Regional Ukrainian National Democratic Organisation. (Timely recollection)”. In it, among other information, the author provides a list of “provisional organisers” of the party from the administrative counties of Eastern Galicia. And this list looks as follows:

1). County Berezhany; Fr. Mykhailo Mossora (Poruchyn) 2) County Horodenka: Dr. Teofil Okunevskyi, 3) County Husiatyn; Fr. Sev. Makhnovskyi (Bossyry) 4) County Kalush: Yaroslav Korytovskyi 5) County Lisko: Fr. Kypriyan Yasenytskyi (Balyhorod) 6) County Skalat: Fr. Yosyp Hankevych (Krasne) 7) County Terebovlia: Fr. Teodor Tsehelskyi (Strusiv ) 8) County Ternopil: Fr. Evst. Tsurkovskyi (Nastasiv) 9) County Zalishchyky: Fr. Hryhoriy Kovch (Lysivtsi) 10) County Zolochiv: Fr. Danylo Taniachkevych, 11) County Zhydachiv: Fr. Severyn Borachok.

It would not be superfluous here to remind that at this congress in 1899 the founders of the UNDP, being law-abiding citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, for the first time in history proclaimed the political goal - obtaining cultural, economic and political independence within a united Ukrainian state in a legal and non-violent way:

“ We, Galician Ruthenians, a part of the Ukrainian-Ruthenian people who have state-building traditions, never renounced and do not renounce the rights of an independent people, declare that the ultimate goal of our national endeavours is to reach the point where the entire Ukrainian-Ruthenian people obtain cultural, economic and political independence and unite over time into a single national organism ”.

One of these figures was Father Hryhoriy Kovch, parish priest of the village of Lysivtsi and Zalishchyky Dean.

In the following years, from 1908 to 1914, he served as the parish priest of the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God in the village of Koshykivtsi of the same Zalishchyky county. At the same time, he oversaw the construction and decoration of the church in Tsapivtsi.

And from 1914 he set off together with son Emilian to the Bosnian town of Kozarac, where he conducted missionary activities among Ukrainian settlers.

From the first days of the proclamation of the ZUNR, Father Hryhoriy Kovch was in the whirl of those events. An elderly man already, a 58-year-old honoured priest. Of course, he had every moral right to return to the parish, survive another war, continue to carry the word of God, raise grandchildren. But no, his conscience did not allow it; at a fateful time for the people, together with his son, he joined the army, was appointed chaplain of a large military formation - the II Galician Corps of the UHA consisting of four brigades (USS, Kolomyia, Berezhany and Zolochiv) under the command of Colonel Myron Tarnavskyi. He fully shared the fate of the Galician Army in 1918 – 1919.

He died on December 19, 1919, in Starokostiantyniv, in the midst of a typhus epidemic. The place of burial in a mass grave is unknown.

Currently, no place of memory about him has been created in the region which he served so sincerely.

* * *

Father Hryhoriy's younger brother, Father Vasyliy Kovch, also deserves a good memory from descendants; his pastoral work is also connected with the Ternopil region (1868, Malyi Liubin, Horodok county – 1941, Kapustyntsi, Chortkiv district, Ternopil region).

If we trust open sources, he received a fine education: graduated from gymnasium in Lviv, Lviv University, studied in Vienna, Prague, Paris, Rome. He knew many foreign languages: Polish, German, Czech, Italian, Latin, Greek, Hebrew.

He was ordained a priest in 1900 by Andrey Sheptytsky, at that time the Bishop of Stanyslaviv.

Father Vasyliy's priestly path lay through Chortkiv county: he served as a coadjutor in the parish in the village of Rosokhach (1900 — 1906), in the village of Ulashkivtsi (1907 — 1909), in the village of Kapustyntsi (1909 – 1914). At the same time, he worked as a school commissioner for villages of Chortkiv and Borshchiv counties: Lanivtsi, Lysivtsi, Shypivtsi, Ulashkivtsi, Sosulivka, Rosokhach, Uhryn, Oleksyntsi.

During the First World War, due to the occupation of Podillia, he was directed to the village of Zarichchia, Nadvirna county.

In the post-war period – long-time parish priest of Kapustyntsi village, Chortkiv county (1918 – 1941). Here he built a large parish house, which in the village is still called the palace. In the 1940s, a “zakhronka” (kindergarten) operated in it under the care of nuns, from 1945 until the beginning of the 21st century – the Kapustyntsi secondary school.

It is known that throughout his life Fr. Vasyliy Kovch wrote extensively, but for unknown reasons did not publish his works. They have also not survived at the parish. There is a theory that the manuscripts were confiscated by the state security organs in 1939. Their further fate is unknown.

According to the priest's metric of Father Vasyliy, preserved in the SIAIFO (State Archives of Ivano-Frankivsk Region), he died on March 28, 1941. He is buried in the village of Kapustyntsi near the church. His modest grave has been preserved and was recently put in order by the church community.

May his memory be eternal!

* * *

Sources of information:

1. Fr. Emilian Kovch – “Why do ours run away from us?” — Lviv, 1932

2. Kovch – Baran A.M., “For God’s Truth and Human Rights: a collection in honour of Fr. Emilian Kovch”. – Saskatoon, 1994

3. State Archives of Ternopil Region, fund 274, inventory 1 – Monthly reports of district commands of the State Police of the Polish Republic

4. Zhanna Kovba – “Humanity in the abyss of hell. The behaviour of the local population of Eastern Galicia during the years of the ‘Final Solution to the Jewish Question’.” Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2009.

5. Zhanna Kovba – “Parish Priest of Peremyshliany and Majdanek” - https://www.ji-magazine.lviv.ua/inform/info-ukr/kovch.htm

6. “Ark of Father Kovch” (collection of journalistic articles), - Kyiv, 2017

7. Newspaper “Dilo” dated 17.09.1933 No. 244 Dr. Yuliy Olesnytskyi – The First Regional Ukrainian National Democratic Organisation

8. Skira Yu. R. – “Participation of monks of the Studite Rule in the rescue of Jews on the territory of the Lviv Archeparchy of the Greek Catholic Church in 1942–1944” – Dissertation for the degree of Candidate of Historical Sciences, Lviv Polytechnic National University, I. Krypiakevych Institute of Ukrainian Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Lviv, 2017.

9. Mykhailo Shkilnyk - “I defended justice as best I could. Memoirs about experiences under the rule of Austria, Poland, the USSR, the Reich”, Ukrainian Catholic University Press, 2017.

10. Oleh Dukh – “If something were to happen to me. Execution of Jews of Peremyshliany in the Berezhyna tract”, Project “Local History”, 2021

11. Kurt Lewin “A Journey Through Illusions”, Svichado Publishing House, 2007

12. Vasyl Drozd – “The Kovch family of pastors in Zalishchyky region” — Chernivtsi: LLC “DrukArt”, 2012.

13. Historical-memoir collection of Chortkiv district. – New York–Paris–Sydney–Toronto, 1974

14. Horbachevskyi Lonhyn - “My life path. For my children and grandchildren in memory” - Montreal-Pierrefonds, 1963

15. Kai Struve – “German Authority, Ukrainian Nationalism, Violence Against Jews. Summer 1941 in Western Ukraine”, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Center for Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry, Kyiv – “Dukh i Litera” Publishing House, 2022, pp. 409 - 411.

16. State Archives of Ivano-Frankivsk Region, fund 504, inventory 1, case 195 a – Register of priests of Stanyslaviv Archeparchy, 1873 – 1944.